Content from Context

Last updated on 2024-12-31 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 10 minutes

Collecting digital data, including 3D data, for the documentation, preservation, study and dissemination of material culture knowledge has been rapidly evolving in the last decades. Such data provide valuable insights about the objects’ biographies and the development of humans within different societal contexts.

With the democratisation of technologies and hence the facilitation of access to equipment, software and sharing of digital data information, digital practices have become established in several domains which aim to investigate human presence and activity, including archaeology, history, ethnography, art and museum studies.

Yet the speed with which technology progresses, the abundance of digital data – often called big data – and the lack of standardisation with regard to digital practices and hence strategies and policies in the digital humanities spectrum, eventfully raise a range of considerations many of which pertain to the realm of ethics. This becomes more prominent, given the possibility to distribute data over the web, customise data and reuse them for various purposes ranging from study to creative activities, as well as physically replicating or reproducing heritage assets through fabrication technologies, such as 3D printing.

As such, ethics become involved in many aspects of the cultural heritage digital data domain. Some of the ethical considerations that might arise when working with cultural heritage data include:

Do we have the approval of material knowledge and object holders to digitise assets?

What are the most appropriate methods to use for digitisation in the given context of our research?

How much data do we need and how will we store it?

Where will we store data and who will we ensure their longevity and preservation?

Who will have access to our data?

What are the secondary uses that we envisage our data will have?

Challenge

Take some time to think about the questions above and how these reflect to your own research project.

Write down some of the main considerations that arise from your project and share with colleagues.

Content from Definition and Considerations

Last updated on 2024-12-31 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

Data ethics refers to the moral principles and guidelines that guide the collection, storage, use, and sharing of data. Data ethics aim to ensure that data-related practices and technologies are used in a responsible and ethical manner, taking into account the potential impact on individuals, society, and the environment. It involves making ethical decisions about how data is collected, processed, and used, as well as addressing issues of bias, discrimination, and inequality that may arise in data-driven activities. All these are incorporated in the main digital data ethical considerations, as described below.

Privacy and Consent

Ensuring that individuals associated with cultural heritage data are informed about how their data will be used and obtaining their consent for its collection and usage.

In the domain of cultural heritage data, privacy and consent are crucial considerations to ensure the ethical treatment of individuals associated with the data. This involves informing individuals about how their data will be used and obtaining their explicit consent for its collection and usage. For example, when digitising human remains or artefacts with identifiable features, researchers should obtain consent from relevant stakeholders, such as descendant communities or cultural representatives, before proceeding with digitisation efforts. Additionally, individuals should be informed about the purposes of digitisation, how the data will be stored, and who will have access to it. Consent processes should be transparent, ensuring that individuals understand the implications of providing their data and have the opportunity to withdraw consent if desired.

Cultural Sensitivity

Respecting the cultural significance of the data and avoiding any actions that may offend or disrespect cultural values or beliefs.

Cultural sensitivity is paramount when dealing with cultural heritage data to avoid actions that may offend or disrespect cultural values or beliefs. Researchers and practitioners should approach the digitisation, analysis and interpretation of cultural artefacts, including endangered knowledge witnesses and human remains, with respect for the cultural significance they hold. This includes consulting with relevant cultural communities or stakeholders to understand their perspectives and preferences regarding the handling of cultural heritage data. Additionally, researchers should be mindful of cultural protocols, traditions, and sensitivities when sharing or disseminating digitised data, ensuring that they are represented accurately and respectfully.

Ownership and Intellectual Property

Clarifying the ownership and rights associated with cultural heritage data, including issues related to intellectual property and copyright.

Clarifying ownership and rights associated with cultural heritage data is essential to address issues related to intellectual property and copyright. Researchers should be transparent about the ownership of digitised data, particularly when collaborating with cultural institutions, communities, or individuals. Clear agreements should be established regarding the rights to access, use, and distribute the data, taking into account the interests and concerns of all parties involved. Additionally, researchers should respect any intellectual property rights associated with cultural artefacts or materials being digitised, obtaining permissions or licenses as necessary to ensure compliance with legal and ethical standards.

Data Security

Implementing measures to protect cultural heritage data from unauthorised access, data breaches, or misuse, safeguarding its integrity and confidentiality.

Ensuring data security is paramount to protect cultural heritage data from unauthorised access, data breaches, or misuse. Researchers and institutions should implement robust security measures to safeguard the integrity and confidentiality of digitised data throughout its lifecycle. This includes encryption protocols, access controls, and regular audits to detect and mitigate potential security threats. Additionally, data storage systems should adhere to industry best practices for information security, complying with relevant regulations and standards to minimise risks to cultural heritage data.

Transparency and Standardisation

Being transparent about the sources of cultural heritage data, the methods used for its collection and analysis, and being accountable for any decisions or actions taken based on the data.

Transparency and standardisation are fundamental principles in the ethical treatment of cultural heritage data. Researchers should be transparent about the sources of data, the methods used for its collection and analysis, and any decisions or actions taken based on the data. This transparency fosters accountability and trust among stakeholders, ensuring that digitisation efforts are conducted ethically and responsibly. Additionally, standardising digitisation and data management practices enables consistency, reproducibility, and comparability across studies, facilitating collaboration and data sharing within the research community. Standardisation in the 3D data heritage domain is still a challenging topic and the digital humanities community is undertaking efforts towards this domain.

Yet, there is still a need to reach a consensus, and such efforts should be supported by adequate infrastructure as well as endeavours to enhance the digital skills capacity of humanities researchers who acquire, deploy, analyse, and share data for research and dissemination purposes.

Reliability

Ethical behaviour requires assessing and minimising errors in digital data, including those introduced during digitisation and reconstruction processes, to ensure the reliability of results.

Ensuring the reliability of cultural heritage data is essential to uphold ethical standards in research and practice. Researchers should assess and minimise errors in digitised data, including those introduced during digitisation and reconstruction processes. This involves validating reconstructed data through quality control measures. Quality control measures refer to the following data quality dimensions (Government Data Quality Hub, 2021):

Accuracy: Ensure data reflects reality, with correct and up-to-date values.

Completeness: Have all necessary data available for a specific purpose, minimising critical omissions.

Uniqueness: Eliminate duplicates to maintain data integrity and trustworthiness.

Consistency: Ensure data values are coherent within records and across datasets.

Timeliness: Ensure data is available when needed, especially in time-sensitive contexts.

Validity: Confirm data adheres to expected formats, types, and ranges, facilitating effective use and automation.

Reliability also includes assessing the methods used for data collection and analysis. By prioritising reliability, researchers can enhance the accuracy and validity of findings derived from cultural heritage data, contributing to the advancement of knowledge and understanding in the field.

Equity and Accessibility

Ensuring equitable access to cultural heritage data for all stakeholders, including marginalised or underrepresented communities, and addressing any barriers to access.

Promoting equity and accessibility is crucial to ensure that cultural heritage data is accessible to all stakeholders, including marginalised or underrepresented communities. Researchers should actively address barriers to access, such as language barriers, technological limitations, or lack of resources, to ensure that diverse interpretations and voices are represented in digitisation and data sharing efforts. Participatory approaches can assist towards this direction. Within this frame, researchers should prioritise inclusivity in data dissemination and sharing practices, making digitised data available in accessible formats and platforms to maximize its utility and impact across diverse audiences.

Data Preservation

Taking measures to preserve cultural heritage data for future generations, including considerations for long-term storage, maintenance, and accessibility.

Preserving cultural heritage data for future generations is a responsibility that requires careful consideration of long-term storage, maintenance, and accessibility. Researchers should implement strategies for data preservation, including robust backup and archival systems, to safeguard digitised data from loss or degradation over time. Additionally, researchers should document metadata and paradata to facilitate data discovery and interpretation by future researchers.

Metadata can be described as data about data, e.g. information about an object in a museum collection which might be visualised through a 3D digital model in a Digital Asset Management System (DAMS)

Paradata can be described as data about processes, e.g. information about the digitisation and post-processing of the 3D model.

By prioritising data preservation, researchers can ensure that cultural heritage data remains accessible and relevant for generations to come, contributing to the ongoing study and appreciation of cultural heritage.

Further information about the preservation of Digital Heritage can be found in UNESCO’s Charter on the Preservation of Digital Heritage, as well as the resources on the websites of the Digital Preservation Coalition and the Community Standards for 3D Data Preservation.

Avoiding Bias and Discrimination

Being aware of and mitigating any biases or prejudices present in cultural heritage data or data analysis processes to prevent discrimination or unfair treatment.

Researchers should be vigilant in avoiding bias and discrimination in cultural heritage data and data analysis processes. This involves critically evaluating potential biases inherent in digitised data, such as sampling biases or cultural biases, and taking steps to mitigate their impact on research outcomes. Researchers should also be mindful of ethical considerations when interpreting digitised data, avoiding interpretations or conclusions that perpetuate stereotypes or marginalise certain groups. By promoting fairness and inclusivity in data collection, analysis, and interpretation, researchers can uphold ethical standards and contribute to a more equitable understanding of cultural heritage.

Challenge

Europeana provides access to millions of assets from heritage institutions across Europe. Go to the website of Europeana https://www.europeana.eu/en, look for assets which are related to your research and find an interesting object.

Examine carefully all the information provided about the object in Europeana (or the providing institution). Can you think about any ethical considerations which might arise by the way that such information has been handled, presented or interpreted?

Team up with a colleague and discuss your comments. Are there any differences or similarities between your findings?

One person from each team shares with the rest of the group their remarks about ethical considerations in data.

Data Protection Act and GDPR

A great amount of data managed by digital humanists in research and practice include information about people. It is important to remember that within ethical conduct, personal data should be protected and hence comply with national and international regulations.

In the UK, the Data Protection Act (DPA) is legislation that governs the processing of personal data. It provides guidelines and regulations on how personal data should be collected, stored, used, and shared. The DPA outlines the rights of individuals regarding their personal data and imposes obligations on organisations that handle such data to ensure its protection. The DPA is essentially the UK’s implementation of the European GDPR.

According to the DPA, personal data should be (Data Protection Act 2018):

- used fairly, lawfully and transparently - used for specified, explicit purposes

- used in a way that is adequate, relevant and limited to only what is necessary

- accurate and, where necessary, kept up-to-date

- kept for no longer than is necessary

- handled in a way that ensures appropriate security, including protection against unlawful or unauthorised processing, access, loss, destruction or damage.

Within this frame, it is particularly necessary to protect sensitive data, which refer to: race; ethnic background; political opinions; religious beliefs; trade union membership; genetics; biometrics; health; sex life or orientation.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a comprehensive data protection law enacted by the European Union (EU) in 2018. The GDPR harmonises data protection laws across all EU member states. It enhances the rights of individuals and imposes stricter obligations on organisations regarding the processing of personal data. These are the main protection and accountability principles according to the GDPR (GDPR 2016):

Lawfulness, fairness, and transparency: These principles must guide the processing of data.

Purpose limitation: Data should be used only for the purposes specified to the data subject when their data was collected.

Data minimization: Only the necessary data should be collected and processed for the specified purposes.

Accuracy: Personal data should be accurate and kept up-to-date.

Storage limitation: Personal data can be stored only for the time that is necessary for the specified purposes.

Integrity and confidentiality: Data processing must ensure the security, integrity, and confidentiality of the data.

Accountability: Data controllers must be able to demonstrate compliance with GDPR regulations.

Key Points

Researchers and practitioners in the cultural heritage domain can responsibly collect, manage, and use data while respecting the rights, values, and interests of all stakeholders involved by considering the following ethical aspects:

- Privacy and Consent

- Cultural Sensitivity

- Ownership and Intellectual Property

- Data Security

- Transparency and Standardisation

- Reliability

- Equity and Accessibility

- Data Preservation

- Avoiding Bias and Discrimination

Content from FAIR and CARE Principles

Last updated on 2024-12-31 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 10 minutes

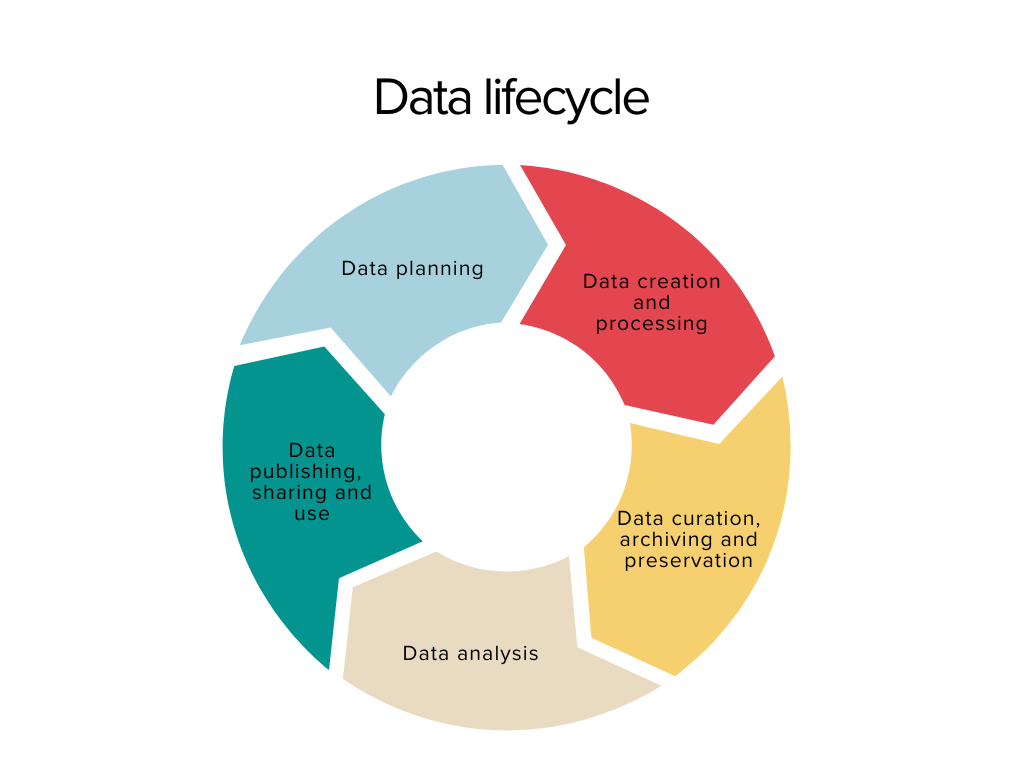

The previous sections discussed the definition of ethics and presented the main considerations that researchers and practitioners should have in mind when dealing with digital data in the heritage domain. All the considerations mentioned about ethics should be taken into account throughout the digital data lifecycle.

For instance, when planning data collection, considerations such as ownership of data and cultural sensitivities must be addressed. Who are the owners or creators of the objects and practices we want to digitise and collect data about? Should we consider cultural sensitivities and potential issues that may arise from collecting such data? Are there biases involved in selecting these objects and associated data? Are our data sufficiently representative?

During data collection, it’s essential to adhere to best practices and standards governing our processes and workflows. Moreover, obtaining full consent for data collection, maintaining transparency about our practices, securing data, and ensuring the reliability of the digitisation and data collection process are crucial.

Therefore, Privacy and Consent, Cultural Sensitivity, Ownership and Intellectual Property, Data Security, Transparency and Standardization, Reliability, Equity and Accessibility, Data Preservation, and Avoiding Bias and Discrimination can constitute a valuable set of considerations to adopt throughout the digital data lifecycle.

In the realm of digital humanities and beyond, FAIR and CARE principles can guide data creators, stakeholders, and publishers in effectively managing ethical data within the Open Data movement. If you’re interested in learning more about the Open Data movement, you can explore this resource provided by the European Commission.

FAIR Principles

The FAIR principles refer to a set of guidelines aimed at enhancing the accessibility and reusability of digital data. FAIR stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. These principles emphasise the importance of making data easy to find, access, integrate with other datasets, and reuse for different purposes. They promote the use of standardised metadata, persistent identifiers, open communication protocols, and clear data usage licenses to ensure that data can be discovered, accessed, and utilised effectively by both humans and machines.

The following actions can help researchers and practitioners to FAIRify data.

Data should be Findable

- Data should be linked to rich and structured metadata.

- Where possible this should be made accessible through a searchable resource such as an aggregation platform.

- Data should be accessible through persistent identifiers (which do not change over time). For example, DOIscan be assigned to data through platforms such as Zenodo or Github.

Data should be Accessible

- Metadata should be accessible via using a protocol for web, such as HTTP/HTTPS which allows to access a webpage over the browser or query a database through a service known as Application Programming Interface (API).

- Where necessary, the protocol show allow for authentication and authorisation to enforce data management rights.

- Consider who will be excluded from access the data, for instance if this is only available via an institutional platform or in a particular language.

Data should be Interoperable

- Consider how other users will bring together content from various data sets, for instance to create a new project.

- For visual media, including images, video and 3D, IIIF (pronounced “triple-eye-eff”) supports interoperability across websites and institutions.

- This framework allows to provide access and shared links to a file, as well as its (meta)data.

- When implemented across many institutions it overcomes data silos.

For example, through IIIF it is possible to bring together objects which physically might be in different locations. It does not require a user to download the files but simply to access the files and metadata over the web.

Data should be Reusable

- Multidimensional data should be released with a clear and accessible data usage license.

- Provenance data will help data not becoming lost.

Key Points

| Principle | Key Points |

|---|---|

| Findability | - Available metadata - Allow for searchability - Persistent IDs |

| Accesibility | - Use web protocols for access - Allow for authorisation - Digital inclusion/exclusion |

| Interoperability | - Data integration - Overcomes data silos - IIIF for visual media |

| Reuse | - License content - Avoid data becoming lost |

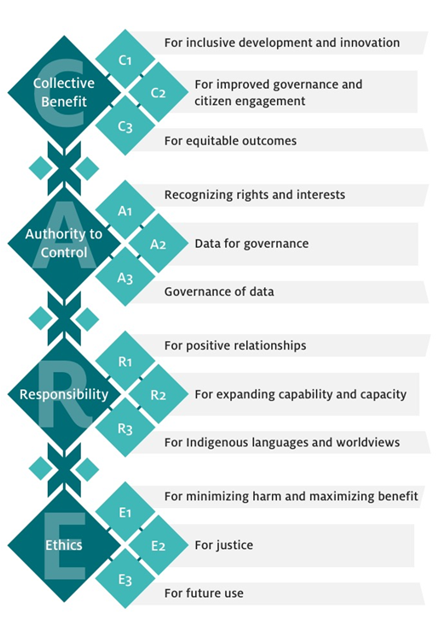

CARE Principles

The CARE principles for Indigenous Data Governance enhance the FAIR principles by adding a social responsibility dimension to open data management practices. Therefore, the data-centric focus of the FAIR principles is complemented by principles emphasising the people (creators, users of data) and the purpose of the data too.

The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance outline key considerations for the ethical and responsible use of Indigenous data. These are presented below (Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group, 2019).

Collective benefit

Data ecosystems should enable Indigenous communities to derive benefit from the data.

- For inclusive development and innovation: Governments and institutions should support Indigenous nations and communities in utilising data for innovation and local development processes.

- For improved governance and citizen engagement: Data should improve planning, engagement, and decision-making. Ethical open data usage boosts transparency and understanding of Indigenous populations, territories, and resources and influences policies affecting Indigenous communities.

- For equitable outcomes: Indigenous data should benefit Indigenous communities equitably, contributing to their aspirations for well-being.

Authority to control

Indigenous people’s rights and authority over Indigenous data must be acknowledged, empowering them to control how their communities and territories are represented.

- Recognising rights and interests: Indigenous communities have collective and individual rights to free, prior, and informed consent in the collection and use of Indigenous data, including the development of data policies and protocols for collection.

- Data for governance: Indigenous communities should have access to data that align with their perspectives and contribute to self-determination and self-governance. Indigenous data should be accessible to people and nations to facilitate Indigenous governance.

- Governance of data: Indigenous communities possess the right to establish cultural governance protocols for Indigenous data and take leadership roles in managing and accessing such data, particularly concerning indigenous knowledge.

Responsibility

Those working with Indigenous data have a responsibility to support Indigenous self-determination and collective benefit, with transparent evidence of these efforts.

- For positive relationships: Relationships built on respect, reciprocity, trust, and mutual understanding should underpin the use of Indigenous data. Such data should respect the dignity of Indigenous people and communities.

- For expanding capability and capacity: Efforts should be made to enhance data literacy within Indigenous communities and support the development of Indigenous data infrastructure and workforce to support data management effectively.

- For Indigenous languages and worldviews: Resources should be provided to generate data grounded in Indigenous languages, worldviews, and lived experiences.

Ethics

Indigenous Peoples' rights and well-being should be the main concern at all stages of the data life cycle.

- For minimising harm and maximising benefit: Ethical data avoid stigmatising Indigenous people or their cultures and are collected in line with Indigenous ethical standards and UNDRIP rights. Assessing ethical benefits and harms should adopt the perspectives of Indigenous communities.

- For justice: Ethical practices address unfair power and resource distributions that affect Indigenous and human rights, and they should include input from relevant Indigenous communities.

- For future use: Data governance should consider future uses and potential harms based on ethical frameworks aligned with Indigenous values. Metadata should indicate origin, purpose, and any restrictions, including consent issues, for secondary use.

Local Contexts

Local Contexts was inspired by Creative Commons, with the objective to create a fresh and supplementary suite of licenses tailored to accommodate the varied intellectual property requirements of Indigenous peoples.

The Local Contexts include two sets of labels to license Indigenous communities knowledge:

The Traditional Knowledge (TK) Labels represent an effort tailored to Indigenous communities. Through extensive collaboration and validation within Indigenous communities spanning various nations, these Labels empower communities to articulate their unique terms for participation in future research and partnerships, aligning with established community norms, governance structures, and protocols governing the use, sharing, and dissemination of knowledge and data. These Labels facilitate the incorporation of local access and usage protocols for cultural heritage that is digitally disseminated beyond the confines of the community.

The Biocultural (BC) Labels establish the standards for how biocultural collections and data should be ethically utilised according to community expectations. They emphasise the importance of precise origin information, openness, and ethical conduct in research collaborations with Indigenous communities.

An effort to accommodate assets within the above context is the Mukurtu Content Management System.

Content from Discourse on Data Ethics

Last updated on 2024-12-31 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

Repatriation

Over the past few decades, there has been a growing discourse surrounding the repatriation and restitution of objects as part of efforts to decolonise and democratise research and practice in the heritage domain.

Several policy documents exist at both national and international levels to guide organisations regarding repatriation requests, dialogue, and the practical steps involved in examining and deciding upon such requests. While these documents primarily focus on the restitution of physical artefacts, they also address the digital data and media accompanying physical assets in collections.

For instance, the Restitution and Repatriation: A Practical Guide for Museums in England by the Arts Council (2023) emphasises the importance of collection information being accessible and transparent by ensuring that:

- Data include comprehensive information about the provenance of collection items, even if they reveal a controversial past.

- Data provide information about the historical context, including how and why items were removed from individuals or communities of origin, and what this reveals about the attitudes of those involved.

- Records are updated with newly discovered information and are accessible to anyone interested in learning more about a museum object or its history.

- Visualisations such as photos and 3D scans are published in an easily searchable format on the organisation’s website, ensuring that the format is accessible across multiple devices, applications, and platforms.

Yet, visualisations might have to be kept confidential if there are requests from claimants or for compliance with legal obligations regarding data protection and databases. Access rights might also have to change based on decision outcomes about the objects of interest. The discussion around digital repatriation and whether digital data should be kept or returned to claimants is also another interesting aspect of this discussion.

The growing interest in the replication of heritage assets through digital fabrication technologies, including 3D printing, is also relevant to repatriation. Several examples of the deployment of this technology in repatriation efforts are described here.

When thinking about physical replication for repatriation purposes, several key considerations include:

- Advanced technological methods can promote discussions on decolonisation and repatriation and should not be regarded as solutions per se.

- Collaboration among cultural heritage institutions, initiative groups, and communities is crucial to enable replication and repatriation.

- Decisions on technology, data sovereignty, access, and replica/object ownership require mutual agreement.

- Diverse perspectives and priorities of communities must be recognised (i.e., reason for repatriation, meaning of object).

- A case-by-case examination is essential, as some communities prioritise making processes or spiritual meaning over originality.

Human remains

The term human remains is used to mean the bodies, and parts of bodies, of once living people from the species Homo sapiens (defined as individuals who fall within the range of anatomical forms known today and in the recent past). This includes osteological material (whole or part skeletons, individual bones or fragments of bone and teeth), soft tissue including organs and skin, embryos and slide preparations of human tissue. (DCMS, 2005)

Please note that the term human remains seems the most popular in literature and policy documents, yet voices are expressing a scepticism or opposition to the term. Some parties have proposed other terms, such as ancestral body or physical evidence of an ancestor (HAD, 2021)

Human remains have long been kept in heritage collections, valued for their contribution to research, education, and the dissemination of knowledge. Studying human remains provides valuable insights into various aspects of history, culture, and biology. From exploring the mysteries of human evolution to understanding past population dynamics and health conditions, such research establishes a direct connection to our ancestors and their lifestyles. This not only enhances our comprehension of the past but also informs contemporary discussions on topics such as health, medicine, and cultural diversity.

The collection, research, study and display of human remains in the UK is guided by governmental and sectorial policy documents, such as the Human Tissue Act (2004), Guidance for the Care of Human Remains in Museums (2005) by the DCMS, the Guidance for Best Practice for the Treatment of Human Remains Excavated from Christian Burial Grounds in England (2017), the Updated Guidelines to the Standards for Recording Human Remains (2017) by the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists, the ICOM Code of Ethics for Natural History Museums (2013), and the ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums (2004). Such documents also provide guidance about the return of human remains when such requests exist.

Most guidance on managing human remains via ethical practices emphasises the need to:

Securely acquire and house collections with human remains and sacred items, respecting professional standards and relevant community beliefs.

Conduct research on these collections with professional standards and consideration for community beliefs.

Display collections with sensitivity to community beliefs and dignity, adhering to professional standards.

Handle requests for removal or return of such items promptly and respectfully, with clear museum policies in place.

With the advancement of powerful and accessible digitisation methods, along with the capacity to visualise data, including representations of human remains, a new dimension is introduced to this discussion. However, there is currently no specific guidance available to address issues related to digitising human remains and managing such digital data. Therefore, the examination and dissemination of digital data about human remains must adhere to the ethical guidance outlined above.

Within this frame, some museums have chosen not to exhibit human remains or images of remains to the public. For instance, the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford not only removed all human remains from the museum displays in 2020, but also disabled access to visualisations of digitised human remains through its online database. These are now available per request and full lists (only with text) of human remains in the museum’s collection are published in pdf format. In this way, the museum aims to facilitate dialogue with communities to decide about the future care or return of remains.

Environmental responsibility

Under the current concerns about climate change and the escalating volume of data, alongside the emergence of AI applications for data management, there is a growing dialogue on environmental responsibility. In the context of digital data, being environmentally responsible involves managing digital information in a way that minimises its negative impact on the environment while ensuring long-term preservation and access.

The main environmental impacts arising from digital activity in the cultural heritage domain and beyond include:

Energy consumption: Infrastructure, including data centres, servers, networks, and end-user devices, requires significant amounts of energy to operate. This energy consumption comes from the continuous need for electricity to power and cool these systems.

Carbon emissions: The majority of the world’s electricity still comes from fossil fuel sources such as coal, oil, and natural gas. When infrastructure relies on electricity generated from these sources, it results in carbon emissions, which contribute to global warming and climate change.

Manufacturing and disposal: The production, distribution, and disposal of equipment also contribute to climate change. The manufacturing process requires energy and raw materials, and the disposal of electronic waste (e-waste) can lead to environmental pollution if not managed properly.

Internet usage: The increasing demand for internet services, streaming media, cloud computing, and data storage contributes to the overall energy consumption of communication technology infrastructure. Data centres, in particular, consume vast amounts of energy to process and store data.

Digitisation: While it has the potential to enable more efficient and sustainable practices in various heritage management processes, the overall increase in digitisation can lead to a net increase in energy consumption and carbon emissions if not managed carefully.

Currently, there is a lack of established guidance to direct decisions and actions toward sustainability goals for digital data management. However, ongoing efforts exist to evaluate the environmental impact of digital activity in the heritage domain and suggest appropriate measures to enhance environmental sustainability.

Some of these efforts include:

The Digital Humanities Climate Coalition Toolkit which aims to help researchers and practitioners to adapt working practices to become more environmentally responsible. The toolkit includes general guidance about hardware, software, data storage, content management systems, use of video and images, the use of AI, as well as grant writing, travelling to work and more.

The Researcher Guide to Writing a Climate Justice-Oriented Data Management Plan which has been published by the same initiative to support with data management planning from a climate justice perspective.

Further guidance by the Digital Heritage Hub provides advice on how to make digital engagement activities more friendly for the environment.

Participatory approaches

Participatory approaches to planning, acquiring, curating and publishing data have been gaining interest and have been adopted by individuals and organisations to overcome ethical considerations and become more inclusive. Participatory research involves collaborative efforts where individuals affected by the research are actively engaged in planning, acquiring, curating and publishing data. Participatory research aims to promote social justice by ensuring that all voices are heard and respected throughout the research process.

While participatory efforts can greatly benefit processes around data throughout their lifecycle, it is important to overcome potential difficulties when working with communities and digital data. Such obstacles might be related to power dynamics, cultural reasons, hidden biases, conflicting individual and community interests, confidentiality in difficult contexts and more.

To leverage participatory approaches when working with data in

collaboration with communities, researchers and practitioners

should:

- Ensuring participants or their representatives have the autonomy to

make informed decisions about their involvement in

research and treating them with dignity throughout the

research process.

Safeguarding the well-being of research participants or communities, minimising potential harm during the research process.

Upholding principles of fairness by equitably distributing the costs and benefits of research, allowing participants access to its outcomes.

Acknowledging the responsibility of researchers to maintain confidentiality, act on matters concerning participant welfare or public safety, and disclose relevant information transparently.

Committing to transparent communication by openly discussing the research purpose and presenting findings truthfully in analysis, presentation, and publication.

Ensuring research contributes positively to society by advancing human knowledge and promoting well-being.

Challenge: Case study reflection

Look at the cases below and think about whether they involve digital data ethical considerations. Then try to write down some responses to the questions below.

Nefertiti hack: resource 1 and resource 2

Tlingit Killer Whale Hat: resource 1

Nomad Project: resource 1

Are there any data ethical considerations which arise from this case?

Were there any considerations concerning FAIR and CARE principles?

How have the different parties responded to the use and sharing of digital data?

What are the implications of this case for the future of discussions about ethics in the digital heritage data domain?

Content from Resources and Further Reading

Last updated on 2024-12-31 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 0 minutes

Arts Council (2023). Restitution and Repatriation: A Practical Guide for Museums. Retrieved from: https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/supporting-arts-museums-and-libraries/supporting-collections-and-cultural-property/restitution-and-repatriation-practical-guide-museums-england

Advisory Panel on the Archaeology of Burials in England (2017). Guidance for Best Practice for the Treatment of Human Remains Excavated from Christian Burial Grounds in England. Retrieved from: https://apabe.archaeologyuk.org/pdf/APABE_ToHREfCBG_FINAL_WEB.pdf

Börjesson, L., Sköld, O. & Huvila, I. (2020). Paradata in Documentation Standards and Recommendations for Digital Archaeological Visualisations. Digital Culture & Society, 6(2), 191-220. https://doi.org/10.14361/dcs-2020-0210

Bouton E. (2018). Replication Ramification: Ethics for 3D Technology in Anthropology Collections. Theory and Practice. Vol.1. 2018. https://articles.themuseumscholar.org/2018/06/11/tp_vol1bouton/

Carew, R. M., French, J., Rando, C., & Morgan, R. M. (2023). Exploring public perceptions of creating and using 3D printed human remains. Forensic Science International: Reports, 7, 100314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsir.2023.100314

Carroll, S. R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodríguez, O. L., Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S., Hudson, M. (2020). The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Science Journal, 19(1), 43.DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2020-043

Centre for Social Justice and Community Action & National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement (2022). Community-based participatory research: A guide to ethical principles and practice (2nd edition), CSJCA & NCCPE, Durham and Bristol. Retrieved from: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-10/d2587_how_ethical_guidance_report_aw.pdf

CS3DP. Community Standards for 3D data preservation. Retrieved from: https://cs3dp.org

DCMS (2005). Guidance for the Care of Human Remains in Museums. Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5f291770e90e0732e4bd8b76/GuidanceHumanRemains11Oct.pdf

DHCC, The digital Humanities Climate Coalition Toolkit. Retrieved from: https://sas-dhrh.github.io/dhcc-toolkit/

DHCC Information, M. and P. A. G. (2022). A Researcher Guide to Writing a Climate Justice Oriented Data Management Plan (v0.6). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6451499

Digital Preservation Coalition. Discover good practice. Retrieved from: https://www.dpconline.org/digipres

Digital shadows: what happens to an artefact’s data after it is restituted? (2023, March 8). The Art Newspaper - International Art News and Events. Retrieved from: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/03/08/digital-shadows-what-happens-to-an-artefacts-data-after-it-is-restituted

Durham Community Research Team. Centre for Social Justice and Community Action, Durham University (2012). Community-based Participatory Research: Ethical Challenges. Retrieved from: https://www.durham.ac.uk/media/durham-university/departments-/sociology/Research-Briefing-9---CBPR-Ethical-Challenges.pdf

GDPR.EU. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) Compliance Guidelines. GDPR.eu. Retrieved from: https://gdpr.eu

GO FAIR initiative: Make your data & services FAIR. GO FAIR. Retrieved from: https://www.go-fair.org

Government Data Quality Hub. (2021). Meet the data quality dimensions. GOV.UK. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/meet-the-data-quality-dimensions

GOV.UK. (2018). Data Protection Act. Gov.uk. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/data-protection

GOV.UK. (2019). Human Tissue Act 2004. Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2004/30/contents

HAD (2021), Definitions for Honouring the Ancient Dead (HAD). Retrieved from: https://www.honour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/HAD-Definitions-2020-v3.pdf

ICOM. (2016). Museums, Ethics and Cultural Heritage. Routledge.

ICOM (2013). Code of Ethics for Natural History Museums. Retrieved from: https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/nathcode_ethics_en.pdf

ICOM. (2017), ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums. Retrieved from: https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ICOM-code-En-web.pdf

IIIF. International Image Interoperability Framework. How it works. Retrieved from: https://iiif.io/get-started/how-iiif-works/

Ireland, T., & Schofield, J. (2016). The ethics of cultural heritage. Springer.

Manžuch, Zinaida (2017) “Ethical Issues In Digitization Of Cultural Heritage,” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies: Vol. 4 , Article 4. Retrieved from: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/jcas/vol4/iss2/4

Mitchell, P. D., Brickley, M., & British Association For Biological Anthropology And Osteoarchaeology. (2017). Updated guidelines to the standards for recording human remains. Chartered Institute For Archaeologists. Retrieved from: https://babao.org.uk/resources/ethics-standards/

NCEAS Learning Hub’s coreR Course - 5 FAIR and CARE Principles. (n.d.). Learning.nceas.ucsb.edu. Retrieved from: https://learning.nceas.ucsb.edu/2023-04-coreR/session_05.html

Parry, K. How to make your digital engagement activities better for the environment. Digital Heritage Hub. Retrieved from: https://www.culturehive.co.uk/digital-heritage-hub/resource/engagement/make-your-digital-engagement-activities-better-for-the-environment/#what-next

Pitt Rivers Museum. Human Remains at the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. www.prm.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved from: https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/human-remains-pitt-rivers-museum-university-oxford

Research Data Alliance International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Interest Group. (September 2019). “CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance.” The Global Indigenous Data Alliance. Retrieved from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d3799de845604000199cd24/t/6397b363b502ff481fce6baf/1670886246948/CARE%2BPrinciples_One%2BPagers%2BFINAL_Oct_17_2019.pdf

Richardson, L-J. (2022). The Dark Side of Digital Heritage: Ethics and Sustainability in Digital Practice. In K. Gartski (Ed.), Critical Archaeology in the Digital Age: Proceedings of the 12th IEMA Visiting Scholar Conference (pp. 201-210). Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0vh9t9jq

Rouhani, B. (2023). Ethically Digital: Contested Cultural Heritage in Digital Context. Studies in Digital Heritage, 7(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.14434/sdh.v7i1.35741

Samaroudi, M. & Rodriguez Echavarria, K. (2019). 3D printing is helping museums in repatriation and decolonisation efforts. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/3d-printing-is-helping-museums-in-repatriation-and-decolonisation-efforts-126449

Sandis, C. (Ed.). (2014). Cultural Heritage Ethics: Between Theory and Practice (1st ed.). Open Book Publishers. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1287k16

UNESCO (2009). Charter on the Preservation of the Digital Heritage. Retrieved from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000179529

UN General Assembly, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007, A/RES/61/295, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/471355a82.html

Halpering J.R. (2019). Is it possible to decolonize the Commons? An interview with Jane Anderson of Local Contexts. Retrieved from: https://creativecommons.org/2019/01/30/jane-anderson/